2018-08-10

I’ve finally got around to publishing my masters thesis in computer science from the University of Bristol.

Quick link: Free Trade: Composable Smart Contracts

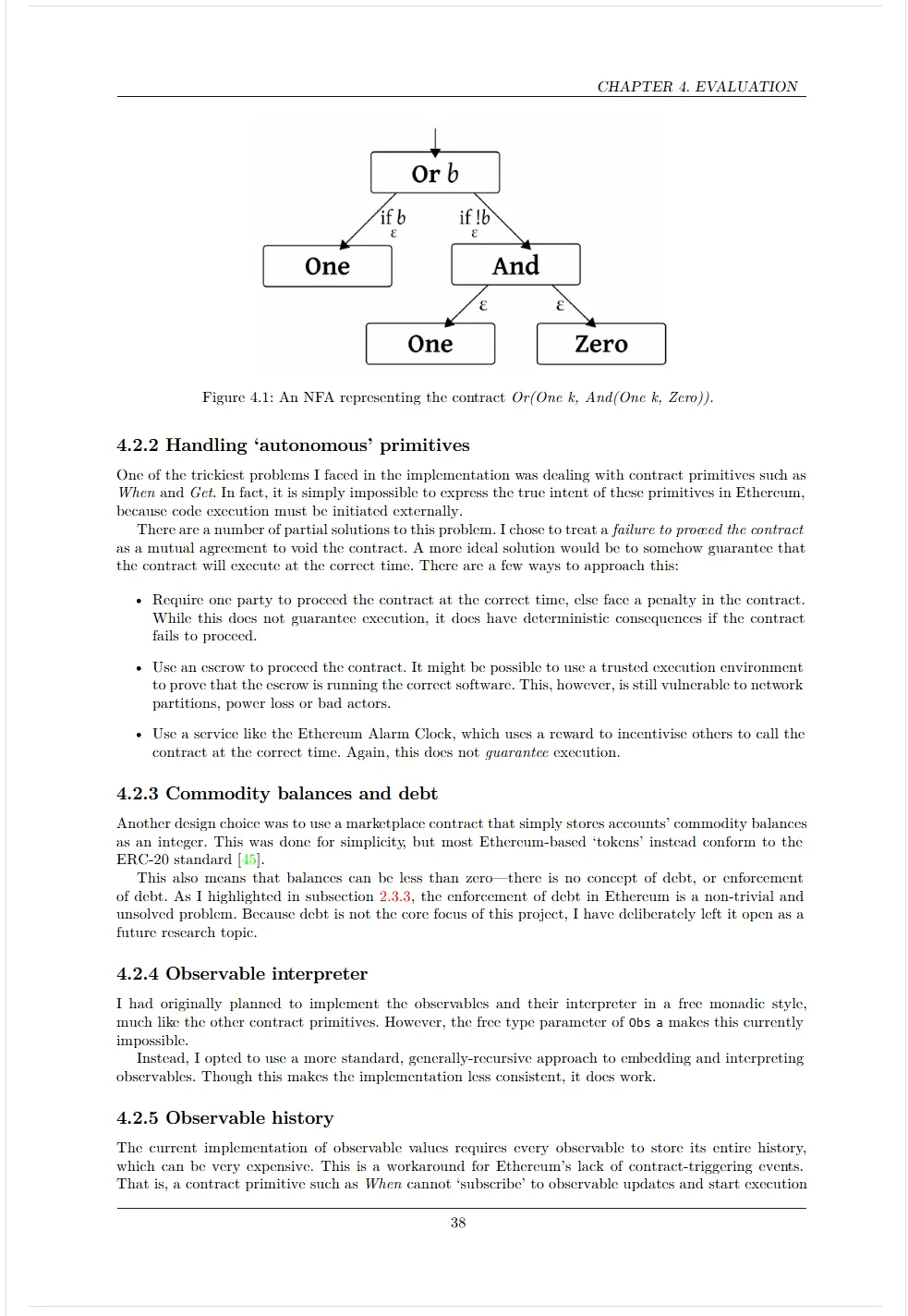

In 2000, Simon Peyton Jones et al. proposed a new combinator language for describing financial contracts. In fact, they appear to have thought this was such a good idea that Peyton Jones and Eber went on to redesign the language and write a book chapter about it.

This expressive domain-specific language was designed to improve on the cumbersome representations of financial contracts used in traditional IT systems. The ultimate goal? It should be possible for financial domain experts to author and analyse contracts without waiting for custom implementation by programmers. For example, you can write a European:

european :: Date -> Contract -> Contract

european t u = when (at t) (u ` or ` zero )Or an American option:

american :: (Date, Date) -> Contract -> Contract

american (t1,t2) u = anytime (between t1 t2) uIn just a line or two of code - and these constructs can themselves be embedded and reused in other contracts. More excitingly, we can have contracts that dynamically change over time in response to outside stimuli. Here’s one that simply scales up and down with respect to some observable volatilityIndex.

c7 :: Currency -> Contract

c7 k = scale volatilityIndex (one k)In July 2015, the Ethereum network was launched. Inspired by Bitcoin’s distributed ‘blockchain’ ledger, Ethereum introduced a critical new feature: smart contracts. In addition to currency transfers, Ethereum allowed network participants to author and deploy actual programs to the blockchain. These smart contracts are now being experimentally applied in a number of areas: prediction markets, stable currencies and so on. Here’s a trivial example: a contract which stores an unsigned integer. Any network participant can set or get the number.

pragma solidity ^0.4.23;

contract SimpleStorage {

uint storedData;

function set( uint x) public {

storedData = x;

}

function get() public constant returns ( uint ) {

return storedData;

}

}More complex contracts can be used for transferring ETH, the Ethereum currency, and representing structures such as auctions, voting systems and ownership ledgers.

I was interested to see if the two technologies - a declarative contract language and smart contracts - could be combined in a useful way. After all, wouldn’t it be useful to be able to write financial smart contracts in a totally declarative way, with no room for errors? It’s all to easy to make a nasty mistake when you try to write contracts by hand.

It turned out that there had been some work in this area by the authors of Findel, but I wanted to prototype an implementation with more advanced features.

I re-implemented the composing contracts language as a free monadic deep embedding in Haskell, then wrote a compiler from the contract language to the Solidity smart contract language. A user can write a contract that looks like the Haskell examples above and compile it directly to Solidity or to a deployable smart contract package.

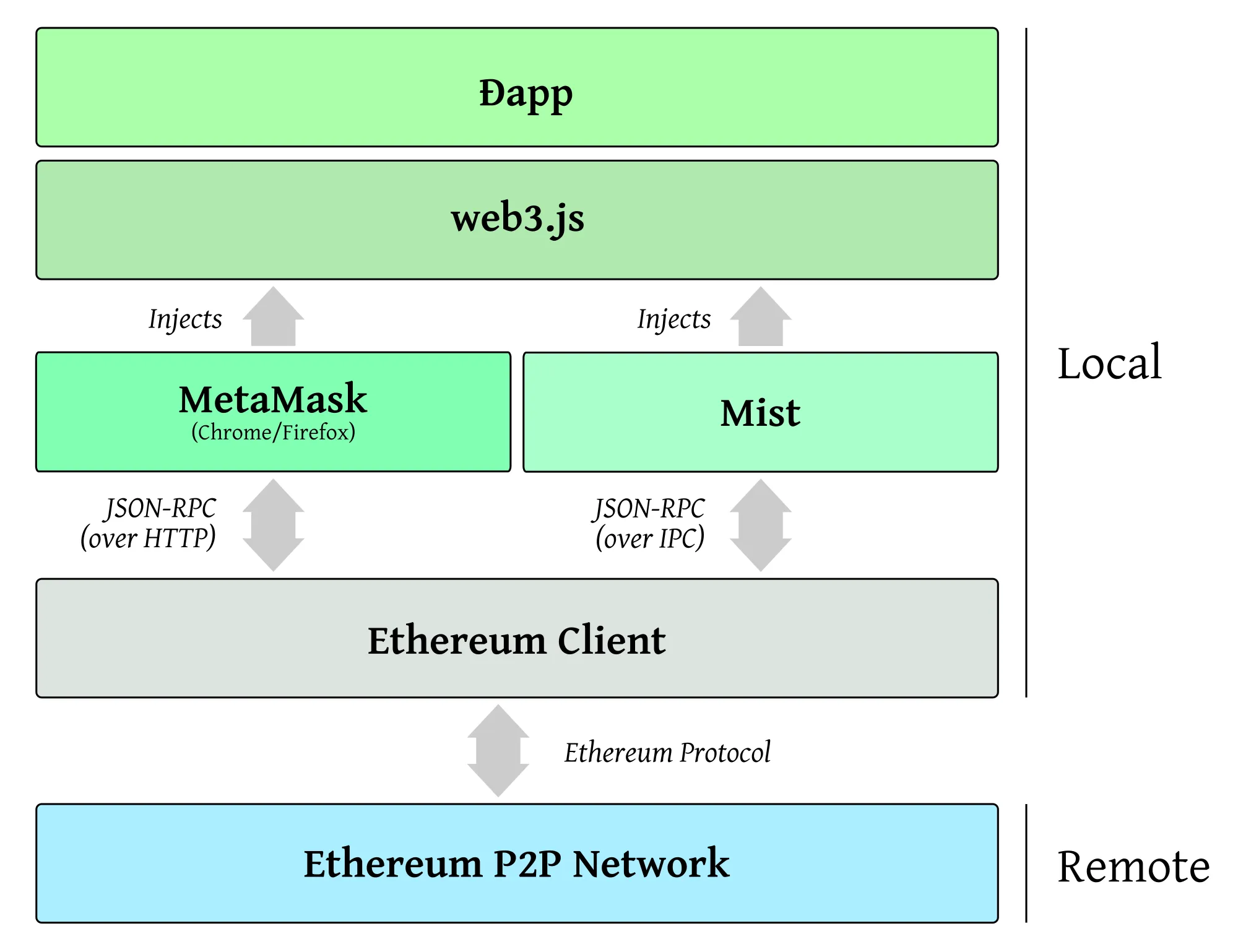

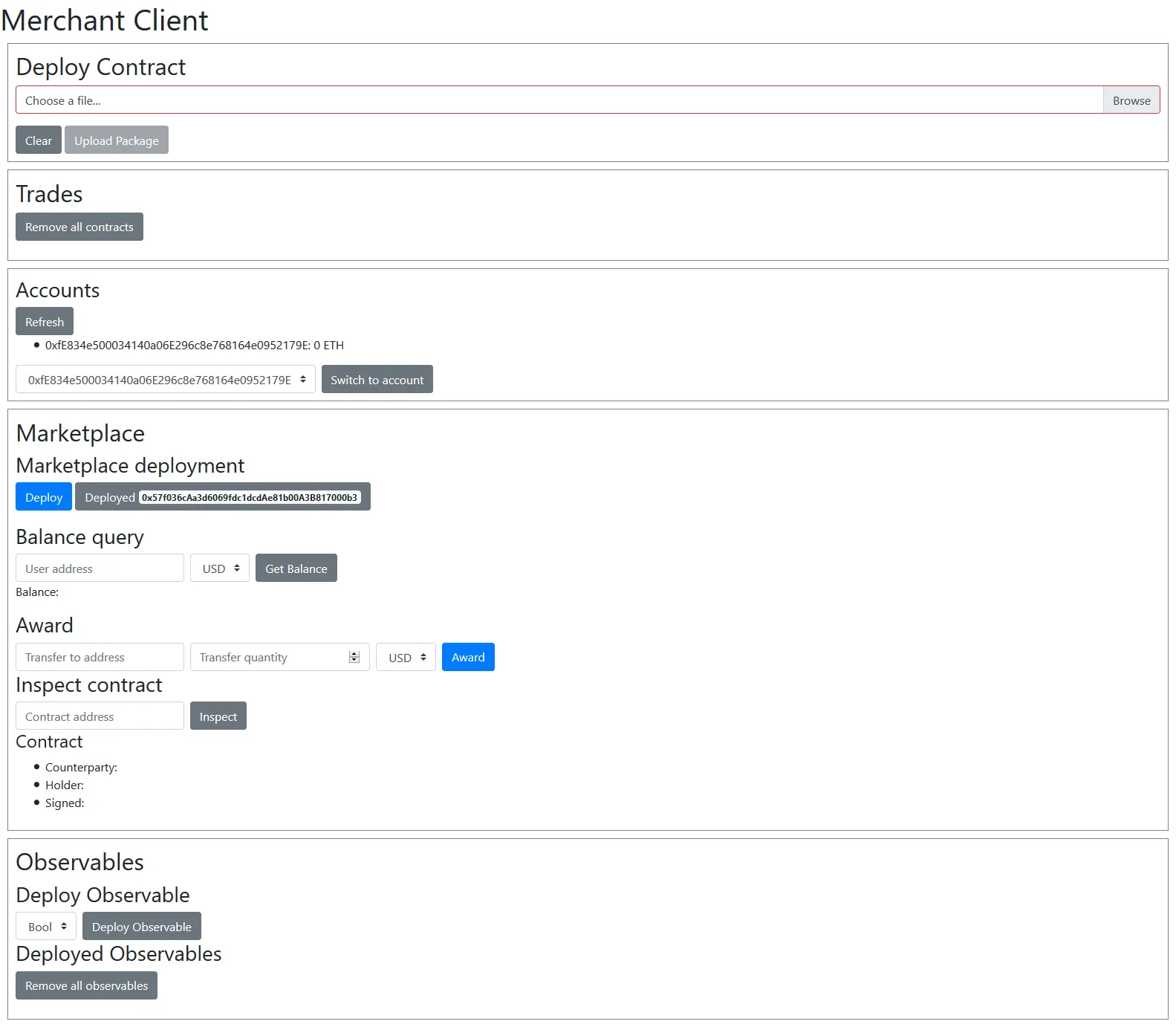

Of course, that isn’t quite enough: we need some way of deploying and managing these contracts on an Ethereum network. I also prototyped a Đapp for deploying, proposing and accepting contracts. Users can upload a JSON contract description, deploy it to the network and then activate it by proposing it to another user.

Is this a viable method for writing Ethereum financial contracts? Well, not today. Ethereum has a few key limitations that make financial contracts quite hard to replicate.

First, it cannot trigger execution of a contract autonomously. That means that contracts cannot perform an action in response to some event. A user must trigger them, at which point the contract can verify that the event has occurred and execute.

Second, there is no widely accepted mechanism for debt enforcement. My prototype implementation simply uses a signed integer balance, not an ERC-20/223 token or ETH itself, but a real world financial market needs debt to function.

The current compiler is not optimising enough for real-world use. In particular, the need to store and test the entire history of observable values is very inefficient and will quickly hit the transaction gas limit.

If you want to know more, I would of course highly recommend reading the full thesis at ResearchGate or Internet Archive 😉. Get in touch or create a GitHub issue if you have any questions.